[ad_1]

The 2011 tsunami in Japan was disastrous, killing nearly 16,000 people, destroying homes and infrastructure, and throwing an estimated 5 million tons of debris out to sea.

However, this rubble did not go away. Some of it drifted all the way across the Pacific and reached the shores of Hawaii, Alaska, and California – and with it came hitchhikers.

Almost 300 different alien species were taken across the ocean in a “mass rafting” event. In 2017, the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center counted 289 Japanese marine species brought to distant coasts after the tsunami, including marine slugs, sea anemones and woodlice, a type of crustacean.

Plastic rafting poses a great and mostly unknown danger. Invasive species that ride to new shores with plastic waste can reduce habitats for native species, transmit diseases (microalgae are a particular threat) and further ecosystems that are already burdened by overfishing and environmental pollution burden. According to David Barnes, a benthic marine ecologist with the British Antarctic Survey and visiting professor at Cambridge University, rafting increases the “risk of extinction”. [while] Decrease in biodiversity, ecosystem functions and resilience â€.

The tsunami also showed something new: Many of the animals survived for more than six years without air, longer than previously thought possible.

Rafting – or oceanic expansion – is a natural phenomenon. Marine organisms attach themselves to marine litter and travel hundreds of kilometers. Free floating tufts of algae like Sargassum, sometimes 3 meters thick, are home to certain types of rafting in the Atlantic, such as reef fish or pipefish and seahorses, both of which are bad swimmers.

Prof. Bella Galil, curator at Tel Aviv University’s Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, said, “Transoceanic rafting is a fundamental feature of marine evolutionary biogeography and ecology that is often used to explain the origins of global patterns of species distribution.”

But while it is relatively rare for an alien species to survive successfully in a new environment, she says that the tremendous increase in litter dumped in the sea, as well as abandoned fishing gear, enables biofouling: aquatic organisms attach themselves to where they are not wanted.

This makes “a rare, sporadic evolutionary process an everyday one,” she says. Invasive species can threaten biodiversity, food security and human well-being. Sea grapes from Australia arriving in the Mediterranean in 1990 displaced other sea algae – a domino effect that ultimately led to a reduction in the number of native snails and crustaceans.

One of the strongest corridors for marine invasions runs from the Red Sea across the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean. Galilee notes that of the 455 alien marine species currently listed in the Eastern Mediterranean, most are believed to have come through the Channel, thanks to the prevailing northerly current or via ballast water, mostly on plastic.

These invasive species don’t just hang around. Many have spread to the central and western Mediterranean and often colonize floating debris. Galil says that some critical habitats are not only adversely affecting, but are also “harmful, poisonous, or poisonous and pose a clear threat to human health”. Long-spiked sea urchins and nomadic jellyfish, both poisonous and both native to the Indian Ocean, are just two examples that are now wreaking havoc in the Mediterranean.

The route is set to become even more popular after the canal’s widening, Egypt’s response to the Ever Given container ship landing earlier this year. “Bigger canal, bigger ships [will mean] larger numbers of Red Sea species are likely to arrive in the Mediterranean, â€says Galil.

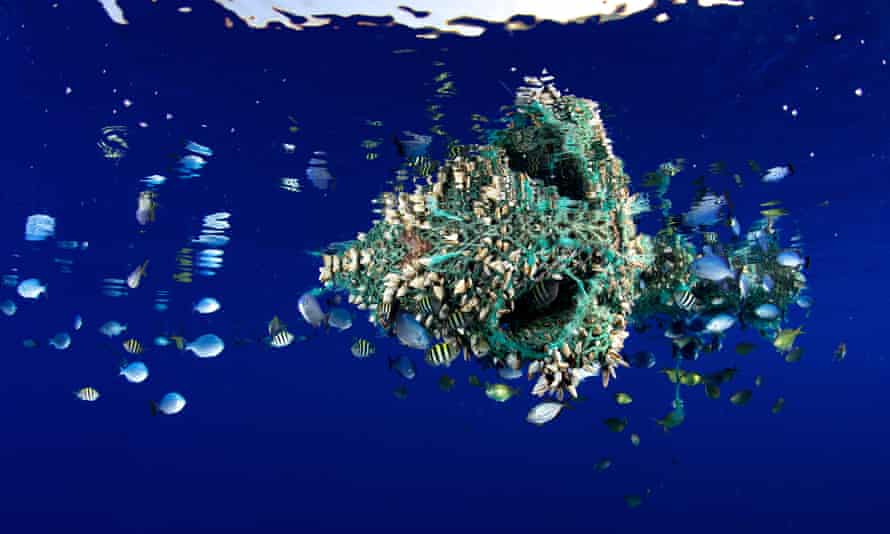

Plastic rafting is by no means limited to the Mediterranean Sea. In the past two decades, the amount of plastic in the ocean has increased a hundredfold in what Barnes calls an “ecosystem changer”.

“Plastic, in particular, has massively increased transport options in terms of the amount of floating debris, its diversity (in size and structure), where it goes and how long it swims,†he says. “In addition, plastic can increase the local distribution of invaders when they arrive and establish themselves.†A 2015 compilation listed 387 species, from microorganisms to algae and invertebrates, that have spilled onto marine litter in “all major marine regions†.

Barnes has even found plastic raft intruders in the Southern Ocean, belittling the notion that Antarctica’s freezing temperatures would keep them in check. Antarctica can be particularly sensitive to such invasions as its endemic species have become almost isolated and evolved within a very narrow range of environmental conditions. “All species that are lost here mean a loss of global biodiversity: They only live in Antarctica, and the blue carbon” [CO2 held in oceans] Storing them provides some strong defenses against climate change, â€he says – blue carbon refers to the carbon stored by marine life like kelp and coral polyps.

With the ocean’s surface now littered with plastic, there are no limits to its travel and it takes invaders with it. Tens of thousands of species can migrate from “anywhere to anywhere, from days to decades,” says Barnes.

One of the most important transport hubs of this maritime expressway network is the North Pacific Gyre, home of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the largest concentration of plastic in our oceans. This is where currents and marine litter converge, and the currents then distribute the litter to the remotest corners of the planet. It is also believed that the South Pacific eddy is responsible for the (mainly plastic) litter on the beaches of Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

According to a 2018 study in the Marine Pollution Bulletin by researchers at the University of Oviedo, Spain, 34% of the debris examined on Easter Island carried organisms from elsewhere. This included water striders, a hard coral called Pocillopora and Airplanes big, a species of crab. Another study by the same authors found plastic rafting along the approximately 200 km long coastline on the Bay of Biscay, with plastic fishing, recreational and household goods carrying non-native invasive species such as the giant Pacific oyster and Australian barnacles.

Some of the world’s most valuable habitats could be threatened, including the Galápagos Islands. With a plastic crisis so bad that 400 pieces of plastic per square meter were found on the islands’ hardest hit beaches, and some of that plastic already known Home to non-native species, it is not difficult to imagine an invasive species that will soon threaten the islands’ famed unique wildlife. Other remote islands such as St. Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha are also “very prone to invasions,” Barnes reported due to “little sea traffic and intact endemic species.”

In 2018, Barnes went a step further, describing marine plastic as an ecosystem in itself, with the only winners being the colonizing fauna, which he called the “plastisphere”.

So what can be done about the plastisphere and who is responsible for it? In connection with the Suez Canal, Galil says: “If we adhere to the polluter pays principle, Europe is complicit – the canal mainly serves Europe.” But she also pleads for an immediate reduction in the amount of plastic in the environment – and “until then strictly enforced ban on ocean dumping â€.

Tracking technologies can also be helpful, such as the Integrated Marine Debris Observing System (IMDOS), a proposed – if not yet implemented – system that combines satellite images, trawl investigations, observations of ships and data transmitted to various organizations in order to gain an overview keep litter in the sea.

Another attempt to standardize the monitoring of marine plastic is Floating Ocean Ecosystems (FloatEco), a multidisciplinary project partially funded by NASA to “better understand the dynamics of floating plastic in open ocean environments.” And there are organizations like Ospar, which bring together 15 governments and the European Union to work together on protecting the Northeast Atlantic.

“A global problem such as plastic litter in the sea and all the challenges associated with it are impossible to solve without cooperation,” says Eva Blidberg, former project manager of Bastic, a current EU initiative for the mapping and monitoring of marine plastic in the Baltic Sea.

But with the pandemic causing an estimated 1.6 million tons of single-use PPE to be thrown away every day, some of which end up in the ocean, the problem only worsens. When Barnes first raised the awareness of the threat of plastic rafting in 2002, he found it difficult to convince people that it was a cause for concern. “Now, in a blizzard of climate and biodiversity issues, society is so in the spotlight that it is still difficult to convince people that it is worth worrying,” he says.

Since it is impossible to prevent organisms from doing what they want, the only real way to stop the raft invaders is to take their rafts away. Monitoring and collaboration are important, says Blidberg, but she adds, “The most important thing is to turn off the tap.”

[ad_2]